There’s a familiar ritual in Warhammer 40,000 circles. A new book drops, a model range expands, a writer leans into the ugliness of the Imperium, and someone inevitably declares that Games Workshop has gotten political. As if the setting – a baroque nightmare of fascism, theocracy, and industrialised death – had ever been anything else.

The truth is simpler, and somehow more uncomfortable: 40K has always been political. Some players just didn’t recognise the politics because they were never the ones being targeted by the satire.

Part 1: The Joke Was Never Subtle

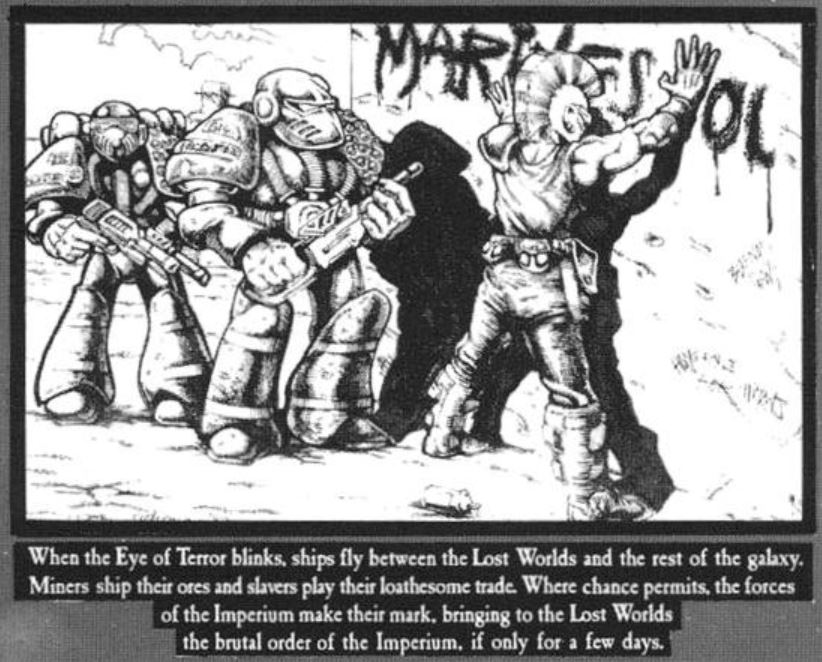

From the very beginning, Warhammer 40,000 wasn’t a straight military setting. It was a joke; a loud, gaudy, aggressively unsubtle joke told by people who were deeply suspicious of power and perfectly willing to mock it. The early writers weren’t trying to smuggle politics into a neutral universe; they were holding up a funhouse mirror to the authoritarian impulses of the late twentieth century and exaggerating them until they became grotesque. The Imperium wasn’t designed to be admired. It was designed to be too much; too cruel, too bureaucratic, too pious, too militarised. A warning dressed up as a wargame.

The satire was everywhere. The Imperium’s bureaucracy was so swollen it became a character in its own right, a kind of cosmic Civil Service (perhaps a DMV for our American cousins?) with skulls glued to it. The Inquisition was a parody of purity culture, a machine that valued suspicion over truth and zeal over competence. Space Marines were propaganda posters made flesh, the state’s ideal soldier stripped of humanity and sold back to the public as salvation. Even the tagline: “In the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war”. This wasn’t a mission statement. It was a punchline. A bleak little wink that said: this is what happens when a society builds itself entirely around fear and obedience.

None of this was subtle. It wasn’t meant to be decoded or excavated. It was meant to hit you in the face. But satire has a strange half‑life. Repeat it long enough and someone will take it seriously. The skulls and eagles that were once exaggerated to the point of absurdity became iconic. The fascist imagery that was meant to be repellent became “cool.” The joke didn’t get quieter; the audience just changed. New players arrived without the cultural context that shaped the early game. Older players grew up with the imagery and forgot the intent. And a vocal minority decided that the satire was never satire at all, that the Imperium was meant to be aspirational, that the cruelty was justified, that the joke was actually a blueprint.

That’s the uncomfortable truth at the heart of this perennial furore: if the satire feels subtle to you, it’s because you weren’t the one it was aimed at. It was always loud. It was always political. It was always pointing at real systems of power and saying, “This is what happens when you stop questioning them.” The only thing that’s changed is how many people mistake the warning for the wallpaper.

Part 2: The Myth of the Apolitical Fandom

There’s a particular kind of amnesia that crops up in long‑running fandoms, and 40K is no exception. You see it whenever someone insists that the setting used to be “just about the battles” or “just cool sci‑fi” before the writers supposedly started “injecting politics.” It’s a comforting story, but it only works if you ignore the actual text. What people are really describing isn’t a political shift in the material, it’s a shift in their own awareness.

For a lot of players, their first encounter with 40K happened at an age when the imagery hit harder than the implications. The skulls, the armour, the gothic excess; all of it landed long before the satire registered. Oppression was just “grimdark.” Fascist aesthetics were just “cool armour.” The Imperium’s cruelty was just “the humans doing what they must.” When you’re young, or new, or simply not attuned to the politics of a thing, you don’t notice the commentary. You just notice the spectacle.

And once you’ve built a private version of the setting in your head – one where the Imperium is heroic, or at least justified – it’s jarring when the official material contradicts that fantasy. Suddenly, the writers are “getting political,” not because they’ve changed anything, but because they’ve made explicit what was always implicit. They’ve said the quiet part at a volume some fans can no longer choose to ignore.

The claim that 40K should be apolitical is really a claim about comfort. It’s a desire to freeze the setting at the exact moment before you realised what it was saying. It’s nostalgia, not for the game itself, but for the feeling of uncomplicated enjoyment. And nostalgia has a way of flattening memory. It turns satire into sincerity, critique into background noise, and politics into something that only exists when it inconveniences you.

But a setting built on authoritarianism, religious extremism, and industrialised warfare cannot be apolitical. It can only be unread. The politics were always there. The only variable is whether you were paying attention.

Part 3: A Setting About Systems, Not Sides

If you strip away the nostalgia and the noise, what 40K has always been interested in is systems; the vast, grinding machinery that shapes people’s lives long before individual choices enter the picture. It’s not a setting that rewards moral clarity or clean ideological lines. It’s a setting where every faction is compromised because every faction is trapped inside structures that are bigger than them. The Imperium isn’t evil because a few bad actors sit on a golden throne; it’s evil because the entire apparatus is built on fear, scarcity, and the belief that survival justifies anything. Chaos isn’t seductive because it offers freedom; it’s seductive because it offers escape from systems so broken that corruption feels like relief. Even the xenos races, often treated as monolithic threats, are shaped by pressures that make their worst impulses inevitable.

This is why the argument that 40K is “just fiction” or “just cool battles” falls apart under the slightest scrutiny. The setting is obsessed with the consequences of systems – bureaucratic, religious, military, economic – and how they warp (hah!) the people inside them. It’s political not because it maps neatly onto modern left‑right divides, but because it understands that politics is the study of power, and power is the only real currency in the grimdark future. Every story in 40K is, at its core, about what happens when institutions become so vast and so rigid that they stop serving the people they were meant to protect. It’s about what gets lost when survival becomes the only moral framework.

And this is where some fans get uncomfortable. Because once you acknowledge that 40K is about systems, you have to acknowledge that those systems resemble real ones. Not perfectly, not allegorically, but recognisably. The Imperium’s cruelty echoes the logic of empires. The Mechanicus mirrors the dangers of dogma masquerading as progress. The Inquisition reflects the paranoia of states that see dissent as treason. None of this is subtle. None of it is accidental. It’s baked into the architecture of the universe.

But it’s far easier to pretend that the setting is apolitical than to confront the fact that the thing you enjoy is critiquing the very structures you might have grown up normalising. It’s easier to focus on the armour and the battles than on the systems that make those battles inevitable. And so the politics get dismissed as “new,” “forced,” or “added in,” when in reality they’ve been there from the first rulebook, just waiting for the reader to catch up.

Part 4: When Satire Becomes Sincerity

Then we come to the strange alchemy that happens to long‑running satire. Repeat a joke often enough and someone will start repeating it back to you without recognising it as a joke at all. Warhammer 40,000 has been around long enough for that transformation to happen in real time. What began as a parody of authoritarian excess has, for a portion of the audience, hardened into something earnest. The skulls, the eagles, the purity seals, all the exaggerated iconography that was meant to signal “this is monstrous,” became aesthetic wallpaper. And once something becomes wallpaper, people stop questioning it.

Part of this is the natural drift of any franchise that outlives its original creators. Early 40K was written by people who assumed their audience would understand the satire because they were steeped in the same cultural moment. It was 1980’s Britain. It was Thatcher’s Britain. But as the game grew, it reached players who didn’t share that context. They encountered the Imperium not as a parody of Empire but as a fully formed fictional empire, complete with heroes, villains, and a visual language that rewarded admiration. The satire didn’t disappear; it just got buried under the weight of its own success.

Another part of this is the way fandoms metabolise meaning. People project themselves into the worlds they love, and in doing so, they sand down the edges that don’t fit. If you want the Imperium to be noble, you can find stories that let you believe that. If you want Space Marines to be uncomplicated heroes, you can read them that way. The setting is vast enough to support almost any interpretation, but that doesn’t mean all interpretations are equally supported by the text. Some are simply more comfortable.

And comfort is powerful. It’s easier to embrace the aesthetics of 40K than to grapple with the critique behind them. It’s easier to celebrate the armour than to acknowledge what the armour is for. It’s easier to treat the Imperium as a power fantasy than as a warning. So the satire gets flattened, the critique gets softened, and the original intent gets lost beneath layers of earnest enthusiasm. The joke becomes sincerity, not because it was written that way, but because it’s easier to live with.

This is why some fans react so strongly when the writers reassert the political edge of the setting. It feels, to them, like an intrusion, as if politics are being “added” rather than restored. But what’s really happening is a collision between two readings: the one the creators intended, and the one the audience constructed. When those readings clash, the satire feels newly sharp, even though it’s been sharp all along.

The irony is that the people who complain the loudest about “politics in 40K” are often the ones who have been living inside the most political interpretation of all, the one where the Imperium is righteous, the violence is justified, and the warning was never meant for them. They didn’t lose the satire. They just outgrew the ability to see it.

Part 5: The Real Question

In the end, the debate over whether 40K is political says far less about the setting than it does about the people arguing over it. The politics have never been hidden. They’ve never been subtle. They’ve never been optional. What changes is the audience’s willingness to see them. For some, the politics were obvious from the first page. For others, they only became visible when the writers stopped trusting the fandom to remember the joke. And for a vocal minority, the politics only “exist” when they contradict the version of the universe they’ve built for themselves.

But that’s the thing about a setting like 40K: it doesn’t care about your comfort. It was never designed to be a safe place to park your power fantasies. It was designed to be abrasive, excessive, and unavoidably critical of the structures it depicts. When the text leans into that, when it reminds you that the Imperium is a nightmare, not a model, it isn’t changing direction. It’s returning to its centre of gravity.

So the real question isn’t whether 40K is political. It always has been. The real question is why some people feel threatened when the politics become impossible to ignore. Maybe it’s the discomfort of realising that the thing you admired was never meant to be admirable. Maybe it’s the shock of discovering that the satire was aimed at the very impulses you found appealing. Or maybe it’s simply the friction that happens when a private fantasy collides with a public text.

Whatever the reason, the politics aren’t new. They’re not an intrusion. They’re not a deviation from some imagined purity of the past. They’re the foundation the entire setting is built on. The only thing that’s changed is who’s paying attention.

Awesome post! I started playing 40k in second edition, and already by then much of the heavy metal gonzo and punk satire inherent to the beginning of the setting had been stripped away–or I was too immature to notice those criticisms of society, despite their relevance to both the Reagan and Thatcher years. The cynical side of me says that playing up the Imperium as “the good guys” is a combination of the darker side of the gaming community and the commercial focus of a business enterprise wanting to focus on as broad an audience as possible.

You’re right to point out the irony of the “no politics in my games” approach common to wargames, video games and RPGs. As you note, that’s flat out impossible. Everything is political in some way or another because the creator’s values are going to show through, however subtly, and this is only more true when we’re exploring constructed societies and fantastic situations which must necessarily contain conflict to be interesting. Most often, I think, when someone says “I don’t want politics in my games,” they mean, “I don’t want your politics in my games.”

I’ll sidestep the problems when not having other politics in a game means embracing facism as a model; you’ve already covered that admirably. For some settings, we need to be able to say “this setting is only fun because it’s not real; this is really nasty stuff.” Since we have a hard time separating artists from art and holding in tension that often the best artists (whether or not felonious or guilty of large-scale ethical infractions) are often not the best people, it shouldn’t be a surprise that we often need to justify the values of a setting to feel that it’s permissible to play in that setting.

As big an issue, if I may be grandiose, is that the “no politics” approach robs fictional settings of integrity, verisimilitude, and artistic value. It’s taken a long time in particular for roleplaying games to become a viable topic of interest in academia, to be recognized as part of a primordial history of human storytelling and a form of art that, while more focused in audience, has the potential to be more intensely meaningful for those who experience it than art for a broader public. Good stories in fantastic settings where the audience participates address the audience directly, and what artist doesn’t dream of that. But, as they say, money ruins everything and it’s little different here–the commodification of what can otherwise be art (whether 40k, D&D or any fictional setting people play in) is so often relegated to a product to be sold. Needing to sell something necessarily leads to it being made as palatable as possible to as many as possible. The strength of the themes and messages of a setting are first lost and then reappropriated in ways that were never intended, that require twisting the original intent. I think of the way so many songs get misinterpreted and misused as symbols of something opposite to original intent. And, of course, that process is decidely political–look at the use of music by the far-right in the U.S. against the complaints of their creators, for example. Despite that example people of all politics would do well to be willing to explore the ideas of other ideologies, being willing to try to understand them without having to agree with them. Games help us do just that.

Maybe the fascism of the Imperium may be a bridge too far on that one, but it doesn’t keep us from looking at the smaller stories in the setting and learning something–one of my favorite things about the Eisenhorn books is that we see an Imperium where people actually have to live rather than the ridiculousness of “only war.”

Anyway, keep up the great work exploring both the fun of the hobby and the deeper meanings! Cheers from the other side of the pond.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a great post, and for putting all of this so nicely into words.

On the one hand, I wonder if the satire about Thatcherism etc is wasted or lost on younger players. But on the other hand, satire about right wing ideology is perhaps more relevant than at almost any time in my life.

LikeLiked by 1 person