The British sitcom is a specific artform that is unique to our little island nation. We do comedy well in a general sense, but it’s hard to beat us in this particular format.

The Americans give us a run for our money, of course. They have some really good sitcoms. I think the problem with their approach is that of scale. Whereas a British sitcom usually consists of 6 to 10 episodes in a series, an American season can often exceed 20 episodes. Whilst the British sitcom is usually written in its entirety by a small team, the American iteration often involves splitting the work between a larger pool of writers. I firmly believe that this is what gives the British sitcom a more consistent feel.

Here are a handful of my favourite classic British sitcoms:

- Blackadder

- Black Books

- Spaced

- Dad’s Army

- Father Ted

- The Thick of It

- Toast of London

- The Thin Blue Line

- Still Game

- The Vicar of Dibley

Honestly, I’m not even scratching the surface there. Purists will no doubt be outraged that Fawlty Towers and Only Fools and Horses are not on the list. They are great shows, of course, but the list above are my favourites.

Another title that belongs firmly in that list is Yes, Minister. Being precise, that would be Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister. The latter was a sequel; a followup to the original series. For the sake of simplicity, I intend to largely conflate the two series into one.

The Review

Yes, Minister is a satire of the workings of government and of the British Civil Service; the relationship and tensions between Westminster and Whitehall. It’s an issue that was relevant at the time the show first aired in the 1980s and it’s still very relevant today. For example, under Johnson, a minister was appointed with the stated goal of reining in the perceived sprawl and waste of the Civil Service, and it’s become common to hear members of the conservative government refer to the entrenched establishment of the Civil Service as “the blob”. Whilst I’m sure that many members of the Civil Service have pretty strong views on the government of the day, they are not as free to speak openly about such things, so as to maintain at least the appearance of their mandated political impartiality.

The show itself focuses on the fictional Department of Administrative Affairs. The series begins in the wake of a general election that sees a change in government. Established MP Jim Hacker is appointed as the minister for this department, and will attend cabinet. Jim is a competent politician, though he is shown to be quite insecure and often displays vanity. None of this is unusual for a senior politician, of course. Something I love about the British political system as opposed to, say, the American one, is that even prime ministers and cabinet ministers are ultimately answerable to their local constituents who can vote them out at the next election.

Jim is consistently frustrated by the Civil Service and their resistance to change. He feels – often correctly – that they are not doing their best to implement his policies, and often seek to undermine him. His relationships with his wife and daughter are also put under considerable strain in the course of the series. Upon arrival in his new department, he meets the permanent secretary (lead civil servant) of the department, Sir Humphrey Appleby.

At the end of Yes, Minister, Jim is chosen by his party to replace the outgoing Prime Minister. At this point, the show becomes Yes, Prime Minister. This is a nice refresh to the series, as it allows us to move on from the issues that cabinet ministers deal with, including the jockeying for the PM’s favour, to the bigger picture issues that the prime minister must address.

Sir Humphrey is a career civil servant, presented as suave and self-assured, though described by his former tutors as “smug” and “too clever by half”. He is well-educated, but is entirely a creature of institution. He spends much of his time attempting to thwart his minister’s plans. This is less out of political opposition to Hacker’s goals and more about ensuring the continued influence and growth of the civil service. My favourite description of Sir Humphrey’s effort to ensure that no government business is done unless it directly benefits the civil service is surmised in the phrase, “creative inertia”.

It is Sir Humphrey’s promotion to cabinet secretary that actually sets in motion the events that lead to the ascension of Jim Hacker to the position of prime minister. As such, when Jim arrives in 10 Downing Street, Sir Humphrey is waiting for him, red boxes in hand to continue to machinations and obfuscations that made Yes, Minister so entertaining.

Jim also meets Bernard Woolley, a younger, less jaded civil servant who acts as his principal private secretary. Bernard experiences split loyalties between his minister and Sir Humphrey and the wider Civil Service in which he expects to have a long and fruitful career. Bernard has less of an established and forceful personality than the two other main characters, but this allows him to walk an interesting line between the two. He acts as a sounding board for both Hacker and Sir Humphrey, and his questions to both often provoke interesting and amusing discussions on the nature of politics, as perceived by each side.

Such is his utility to his minister that Jim takes Bernard with him to Downing Street when he becomes Prime Minister. In this role, Bernard continues to find his loyalties tested by both men and he is often split on who to support.

There are a number of other characters, of course. These range from recurring roles such as Mrs Hacker, the cabinet secretary, Sir Arnold, and Jim’s political advisers, through to one-off characters such as union reps, department officials, interviewers, politicians and the like. Even then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher made an appearance in one memorable episode.

Episodes tend to focus around a specific issues, exploring the intricacies and intrigues thereof. For example, the first series has episodes that focus on the following issues:

- Open Government

- Relationships with oil-rich regimes

- Government budget cuts

- Data protection

- Civil Service restructuring

- Environmentalism/animal protection

- Government waste

What’s interesting about this list is that these continue to be relevant and important issues today. Hell, there’s a hugely controversial sporting event going on in a distant desert right now that would simply not be happening if the host nation and their less-than-savoury regime were not slick with oil-money.

This timelessness is what really sets the show apart, as well as a staunch refusal to state unequivocally where on the political spectrum the government, of which Jim Hakker is first a part and later the leader, lies. I think this is good for keeping the audience onside. You’re never automatically doubting actions or policies on the basis of party affiliation. I mean, as a minister in a majority government with no coalition partner, Jim is clearly either Labour or Conservative. He’s no Lib Dem, Green, SNP, Independent, DUP, Sinn Fein, or the like. Actually, I suppose nobody was Lib Dem at the time as the show took place before the 1988 merger of the Liberal party with Social Democratic Party. Whatever the case, I think the ambiguity helps.

Between the relatable, timeless stories, the fantastic performances of the main cast, and the scathing take on the British political establishment, and just good, old-fashioned compelling storytelling, Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister remains an absolute classic. It’s a sitcom in the finest tradition of that genre. It’s also a series that works just as well on radio as on TV, and I find myself regularly re-listening to my favourite episodes via Audible.

Just, maybe skip the 2013 revival, eh?

As much as I adore David Haig, it just wisnae that good, y’know? I did love Robbie Coltrane’s performance in it, though.

Play Suggestion

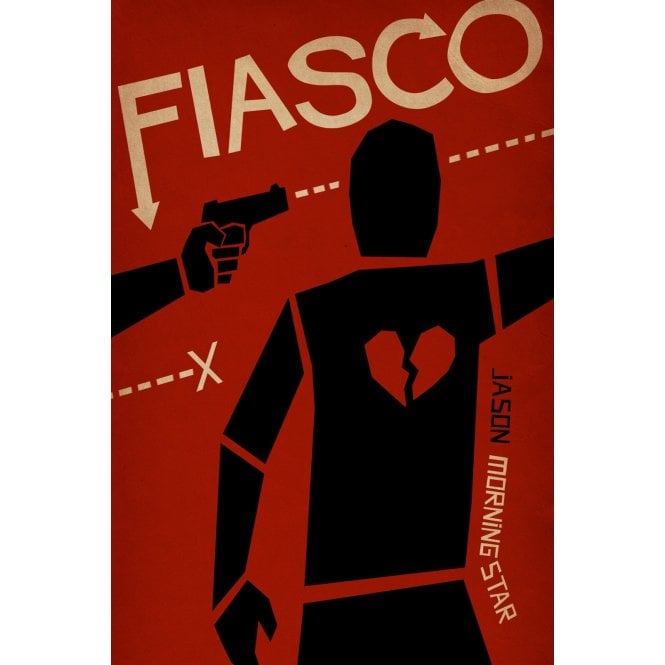

In my review of Wednesday, I had a lot of suggestions for games that could be used to play out the series in an RPG context. For Yes, Minister I have fewer suggestions. In fact, I have just a single suggestion, and that is Fiasco:

Fiasco would likely be my suggestion for most RPG adaptations of sitcoms. Oh, sure, you could use FATE. You can use FATE for anything. The thing is, Yes, Minister is all about relationships, interactions, misunderstandings, and discussion. This is what Fiasco’s all about, son! Add in the obligatory dash of comedic improv and you’ve got yourself a good time.

I’ve not found a good, appropriately themed Fiasco playset to use for games specifically themed around UK politics, but I have played other political games. I had a lot of fun with the Election Night playset, for example. Fiasco is definitely the only way to really capture Yes, Minister in game form.

11 Comments